Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein.

Topic Contents

- General Information About Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

- Cellular Classification of Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

- Stage Information for Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

- Treatment Option Overview for Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

- Treatment of Stage I Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

- Treatment of Stage II Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

- Treatment of Stage III Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

- Treatment of Stage IV Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

- Treatment of Recurrent Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

- Latest Updates to This Summary (09 / 18 / 2024)

- About This PDQ Summary

Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

General Information About Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

Incidence and Mortality

Germ cell tumors of the ovary are uncommon but aggressive tumors, seen most often in young women and adolescent girls. These tumors are frequently unilateral and are generally curable if found and treated early. The use of combination chemotherapy after initial surgery has dramatically improved the prognosis for many women with these tumors.[1,2,3]

Dysgerminomas

One series found a 10-year survival rate of 88.6% following conservative surgery for patients with dysgerminoma confined to the ovary; smaller than 10 cm in size; with an intact, smooth capsule unattached to other organs; and without ascites.[4] A number of patients had one or more successful pregnancies following unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.[4] Even patients with incompletely resected dysgerminoma can be rendered disease free following chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) or a combination of cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin.[5]

Other Germ Cell Tumors

A report of 35 cases of germ cell tumors, half of which were advanced stage or recurrent or progressive disease, demonstrated a 97% sustained remission at 10 months to 54 months after the start of a combination of BEP.[1] Two Gynecologic Oncology Group trials reported that 89 of 93 patients with stage I, II, or III disease who had completely resected tumors were disease free after three cycles of BEP.[1,3]

Endodermal sinus tumors of the ovary are particularly aggressive. A review of the literature in 1979 prior to the widespread use of combination chemotherapy found only 27% of 96 patients with stage I endodermal sinus tumor alive at 2 years after diagnosis. More than 50% of the patients died within a year of diagnosis.

Patients with mature teratomas usually experience long-term survival, but survival for patients with immature teratomas after surgery only is related to the grade of the tumor, especially its neural elements. In a series of 58 patients with immature teratoma treated before the modern chemotherapeutic era, recurrence was reported in 18% of the patients with grade 1 disease, 37% of the patients with grade 2 disease, and 70% of the patients with grade 3 disease.[6] Similar findings have been reported by others.[7]

Some studies have found that size and histology were the major factors determining prognosis for patients with malignant mixed germ cell tumors of the ovary.[6,8] Prognosis was poor for patients with large tumors when more than one-third of the tumor was composed of endodermal sinus elements, choriocarcinoma, or grade 3 immature teratoma. When the tumor was smaller than 10 cm in diameter, the prognosis was good, regardless of the composition of the tumor.[8,9]

References:

- Gershenson DM: Update on malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. Cancer 71 (4 Suppl): 1581-90, 1993.

- Segelov E, Campbell J, Ng M, et al.: Cisplatin-based chemotherapy for ovarian germ cell malignancies: the Australian experience. J Clin Oncol 12 (2): 378-84, 1994.

- Williams S, Blessing JA, Liao SY, et al.: Adjuvant therapy of ovarian germ cell tumors with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin: a trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 12 (4): 701-6, 1994.

- Thomas GM, Dembo AJ, Hacker NF, et al.: Current therapy for dysgerminoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol 70 (2): 268-75, 1987.

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, Hatch KD, et al.: Chemotherapy of advanced dysgerminoma: trials of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 9 (11): 1950-5, 1991.

- Norris HJ, Zirkin HJ, Benson WL: Immature (malignant) teratoma of the ovary: a clinical and pathologic study of 58 cases. Cancer 37 (5): 2359-72, 1976.

- Gallion H, van Nagell JR, Powell DF, et al.: Therapy of endodermal sinus tumor of the ovary. Am J Obstet Gynecol 135 (4): 447-51, 1979.

- Kurman RJ, Norris HJ: Malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. Hum Pathol 8 (5): 551-64, 1977.

- Murugaesu N, Schmid P, Dancey G, et al.: Malignant ovarian germ cell tumors: identification of novel prognostic markers and long-term outcome after multimodality treatment. J Clin Oncol 24 (30): 4862-6, 2006.

Cellular Classification of Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

The following histological subtypes have been described.[1,2]

- Dysgerminoma.

- Other germ cell tumors:

- Endodermal sinus tumor (rare subtypes are hepatoid and intestinal).[1]

- Embryonal carcinoma.

- Polyembryoma.

- Choriocarcinoma.

- Teratoma:

- Immature.

- Mature:

- Solid.

- Cystic:

- Dermoid cyst (mature cystic teratoma).

- Dermoid cyst with malignant transformation.

- Monodermal and highly specialized:

- Struma ovarii.

- Carcinoid.

- Struma ovarii and carcinoid.

- Others (e.g., malignant neuroectodermal and ependymoma).

- Mixed forms.

References:

- Gershenson DM: Update on malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. Cancer 71 (4 Suppl): 1581-90, 1993.

- Serov SF, Scully RE, Robin IH: International Histologic Classification of Tumours: No. 9. Histological Typing of Ovarian Tumours. World Health Organization, 1973.

Stage Information for Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

In the absence of obvious metastatic disease, accurate staging of germ cell tumors of the ovary requires laparotomy with careful examination of the following:

- Entire diaphragm.

- Both paracolic gutters.

- Pelvic nodes on the side of the ovarian tumor.

- The para-aortic lymph nodes.

- The omentum.

The contralateral ovary should be carefully examined and biopsied if necessary. Ascitic fluid should be examined cytologically. If ascites is not present, it is important to obtain peritoneal washings before the tumor is manipulated. In patients with dysgerminoma, lymphangiography or computed tomography is indicated if the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes were not carefully examined at the time of surgery.

Although not required for formal staging, it is desirable to obtain serum levels of alpha fetoprotein and human chorionic gonadotropin as soon as the diagnosis is established because persistence of these markers in the serum after surgery indicates unresected tumor.

The Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) Staging

The FIGO and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) have designated staging to define ovarian germ cell tumors; the FIGO system is most commonly used.[1,2]

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[1] | ||

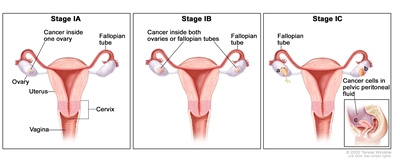

| I | Tumor confined to ovaries or fallopian tube(s). |

|

| IA | Tumor limited to one ovary (capsule intact) or fallopian tube; no tumor on ovarian or fallopian tube surface; no malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings. | |

| IB | Tumor limited to both ovaries (capsules intact) or fallopian tubes; no tumor on ovarian or fallopian tube surface; no malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings. | |

| IC | Tumor limited to one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, with any of the following: | |

| IC1: Surgical spill. | ||

| IC2: Capsule ruptured before surgery or tumor on ovarian or fallopian tube surface. | ||

| IC3: Malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings. | ||

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[1] | ||

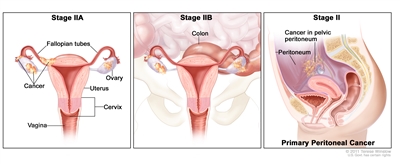

| II | Tumor involves one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes with pelvic extension (below the pelvic brim) or primary peritoneal cancer. |

|

| IIA | Extension and/or implants on uterus and/or fallopian tubes and/or ovaries. | |

| IIB | Extension to other pelvic intraperitoneal tissues. | |

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[1] | ||

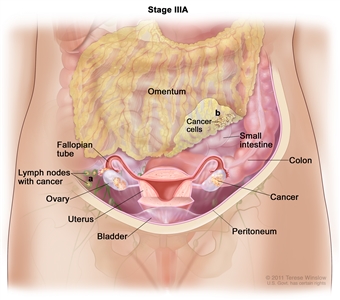

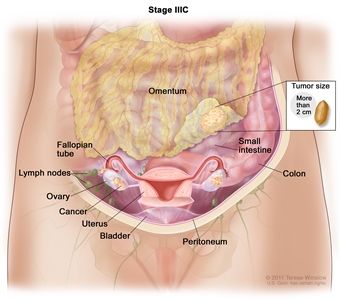

| III | Tumor involves one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or primary peritoneal cancer, with cytologically or histologically confirmed spread to the peritoneum outside the pelvis and/or metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. | |

| IIIA1 | Positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes only (cytologically or histologically proven): |

|

| IIIA1(I): Metastasis ≤10 mm in greatest dimension. | ||

| IIIA1(ii): Metastasis >10 mm in greatest dimension. | ||

| IIIA2 | Microscopic extrapelvic (above the pelvic brim) peritoneal involvement with or without positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes. | |

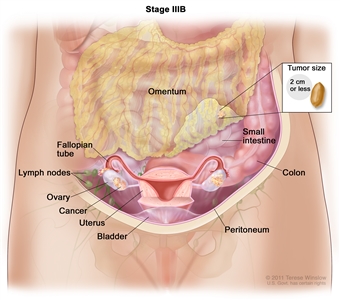

| IIIB | Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis ≤2 cm in greatest dimension, with or without metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. |

|

| IIIC | Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis >2 cm in greatest dimension, with or without metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (includes extension of tumor to capsule of liver and spleen without parenchymal involvement of either organ). |

|

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[1] | ||

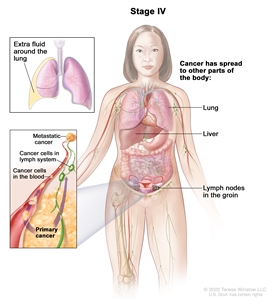

| IV | Distant metastasis excluding peritoneal metastases. |

|

| IVA | Pleural effusion with positive cytology. | |

| IVB | Parenchymal metastases and metastases to extra-abdominal organs (including inguinal lymph nodes and lymph nodes outside of the abdominal cavity). | |

References:

- Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, et al.: Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 155 (Suppl 1): 61-85, 2021.

- Ovary, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 681-90.

Treatment Option Overview for Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

Treatment options for patients with ovarian germ cell tumors include:

- Surgery.

- Chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy.

- High-dose chemotherapy with bone marrow transplant (under clinical evaluation).

Patients may be treated with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

All patients except those with stage I, grade I immature teratoma and stage IA dysgerminoma require postoperative chemotherapy. With platinum-based combination chemotherapy, the prognosis for patients with endodermal sinus tumors, immature teratomas, embryonal carcinomas, choriocarcinomas, and mixed tumors containing one or more of these elements has improved dramatically.[1] As new and more effective drugs are developed, many of these patients will be candidates for newer clinical trials.

References:

- Gershenson DM, Morris M, Cangir A, et al.: Treatment of malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 8 (4): 715-20, 1990.

Treatment of Stage I Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

Dysgerminomas

Treatment options for stage I dysgerminomas include:

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with or without lymphangiography or computed tomography (CT).

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy followed by observation.

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

For patients with stage I dysgerminoma, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy conserving the uterus and opposite ovary is accepted treatment of the younger patient who wants to preserve fertility or a pregnancy. Postoperative lymphangiography or CT is indicated before treatment decisions are made for patients who have not had careful surgical and pathological examination of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes during surgery.

Patients who have been completely staged and have stage IA tumors may be observed carefully after surgery without adjuvant treatment. About 15% to 25% of these patients will relapse, but they can be treated successfully at the time of recurrence with a high likelihood of cure.

Incompletely staged patients or those with higher stage tumors should probably receive adjuvant treatment. Options include radiation therapy or chemotherapy. A disadvantage of the former is loss of fertility resulting from ovarian failure. Experience with adjuvant chemotherapy is limited, but considering the effectiveness of chemotherapy in tumors other than dysgerminoma and in advanced stage dysgerminoma, adjuvant chemotherapy is likely to be very effective and to allow recovery of reproductive potential in patients with an intact ovary, fallopian tube, and uterus.[1]

Other Germ Cell Tumors

Treatment options for patients with other stage I germ cell tumors include:

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy followed by observation.

For patients with stage I germ cell tumors, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed when fertility is to be preserved. For all patients with tumors other than pure dysgerminoma and low-grade (grade I) immature teratoma, chemotherapy is usually given postoperatively, although a series demonstrated excellent survival for patients with all types of stage I tumors managed by surveillance, reserving chemotherapy for cases in which postsurgery recurrence is documented.[2][Level of evidence C1]

There is considerable experience with a combination of vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide (VAC) given in an adjuvant setting. However, combinations containing cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin (BEP) are now preferred because of a lower relapse rate and shorter treatment time.[3] While a prospective comparison of VAC versus BEP has not been performed, in well-staged patients with completely resected tumors, relapse is rare following platinum-based chemotherapy.[3] However, the disease will recur in about 25% of well-staged patients treated with 6 months of VAC.[4]

Evidence suggests that second-look laparotomy is not beneficial in patients with initially completely resected tumors who receive cisplatin-based adjuvant treatment.[5,6]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Thomas GM, Dembo AJ, Hacker NF, et al.: Current therapy for dysgerminoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol 70 (2): 268-75, 1987.

- Dark GG, Bower M, Newlands ES, et al.: Surveillance policy for stage I ovarian germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 15 (2): 620-4, 1997.

- Williams S, Blessing JA, Liao SY, et al.: Adjuvant therapy of ovarian germ cell tumors with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin: a trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 12 (4): 701-6, 1994.

- Slayton RE, Park RC, Silverberg SG, et al.: Vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide in the treatment of malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study (a final report). Cancer 56 (2): 243-8, 1985.

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, DiSaia PJ, et al.: Second-look laparotomy in ovarian germ cell tumors: the gynecologic oncology group experience. Gynecol Oncol 52 (3): 287-91, 1994.

- Gershenson DM: The obsolescence of second-look laparotomy in the management of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol 52 (3): 283-5, 1994.

Treatment of Stage II Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

Dysgerminomas

Treatment options for patients with stage II dysgerminomas include:

- Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Clinical trials.

For patients with stage II dysgerminoma, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are usually performed. For the younger patient who wants to preserve fertility, a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may be considered standard therapy, depending on the age of the patient, and adjuvant chemotherapy should be given.

These patients should receive adjuvant treatment. Options include radiation therapy or chemotherapy. A disadvantage of the former is loss of fertility resulting from ovarian failure. Experience with adjuvant chemotherapy is limited, but considering the effectiveness of chemotherapy in tumors other than dysgerminoma and its effectiveness in advanced-stage dysgerminoma, adjuvant chemotherapy is likely to be effective and to allow recovery of reproductive potential in patients with an intact ovary, fallopian tube, and uterus. Thus, adjuvant chemotherapy with the combination of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) has replaced radiation therapy except in the rare patient in whom chemotherapy is not considered appropriate.

Other Germ Cell Tumors

Treatment options for patients with other stage II germ cell tumors include:

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Second-look laparotomy.

- Clinical trials.

For patients with stage II germ cell tumors other than pure dysgerminoma, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed when fertility is to be preserved. Although there is considerable experience with the combination of vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide (VAC), especially when given in an adjuvant setting, BEP is more effective.[1,2,3] Patients who do not respond to a cisplatin-based combination may still attain a durable remission with VAC as salvage therapy.[4] Recurrence after three courses of BEP as adjuvant therapy is rare.[4] All patients who do not respond to standard therapy are candidates for clinical trials. When there is residual disease or elevated levels of alpha-fetoprotein or human chorionic gonadotropin after maximal surgical debulking, three or four courses of BEP combination chemotherapy are indicated.[5]

Evidence suggests that second-look laparotomy is not beneficial in patients with initially completely resected tumors who receive cisplatin-based adjuvant treatment.[6] Second-look surgery may be of benefit for a minority of patients whose tumor was not completely resected at the initial surgical procedure and who had teratomatous elements in their primary tumor.[6,7] Surgical resection of residual masses detected by clinical examination, by radiographic procedures, or at re-exploration should be undertaken since reversion to germ cell tumor has been described.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Williams S, Blessing JA, Liao SY, et al.: Adjuvant therapy of ovarian germ cell tumors with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin: a trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 12 (4): 701-6, 1994.

- Pinkerton CR, Pritchard J, Spitz L: High complete response rate in children with advanced germ cell tumors using cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 4 (2): 194-9, 1986.

- Gershenson DM, Morris M, Cangir A, et al.: Treatment of malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 8 (4): 715-20, 1990.

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, Moore DH, et al.: Cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin in advanced and recurrent ovarian germ-cell tumors. A trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med 111 (1): 22-7, 1989.

- Williams SD, Birch R, Einhorn LH, et al.: Treatment of disseminated germ-cell tumors with cisplatin, bleomycin, and either vinblastine or etoposide. N Engl J Med 316 (23): 1435-40, 1987.

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, DiSaia PJ, et al.: Second-look laparotomy in ovarian germ cell tumors: the gynecologic oncology group experience. Gynecol Oncol 52 (3): 287-91, 1994.

- Gershenson DM: The obsolescence of second-look laparotomy in the management of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol 52 (3): 283-5, 1994.

Treatment of Stage III Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

Dysgerminomas

Treatment options for patients with stage III dysgerminomas include:

- Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Clinical trials.

For patients with stage III dysgerminoma, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are recommended with removal of as much gross tumor as can be done safely without resection of portions of the urinary tract or large segments of the small or large bowel. Patients who want to preserve fertility may be treated with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy if chemotherapy is to be used.[1,2,3,4,5]

Combination chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) can cure most of these patients. In a report of results from two Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) trials, 19 of 20 patients with incompletely resected tumors who were treated with BEP or cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin (PVB) were disease free at a median follow-up of 26 months.[1] When there is bulky residual disease, it is common to give three to four courses of a cisplatin-containing combination such as PVB or BEP.[6,7,8] A randomized study in testicular cancer has shown that bleomycin is an essential component of the BEP regime when only three courses are given.[9] Because chemotherapy with BEP appears to be less sterilizing than wide-field radiation, combination chemotherapy is the preferred treatment in the patient who wants to preserve fertility.[1]

Other Germ Cell Tumors

Treatment options for patients with other stage III germ cell tumors include:

- Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy, with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy, with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Second-look laparotomy.

- Clinical trials.

For patients with stage III germ cell tumors other than pure dysgerminoma, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended with removal of as much tumor in the abdomen and pelvis as can be done safely without resection of portions of the urinary tract or large segments of the small or large bowel. Patients who wish to preserve fertility can be treated with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.[1,3,4] For patients with extensive intra-abdominal disease whose clinical condition precludes debulking surgery, chemotherapy can be considered prior to surgery. Following maximal surgical debulking, three to four courses of cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy are indicated.[2,6,10]

Evidence suggests that second-look laparotomy is not beneficial in patients with initially completely resected tumors who receive cisplatin-based adjuvant treatment.[11] Patients who do not respond to a cisplatin and etoposide-based combination may still attain a durable remission with a combination of vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide or a combination of cisplatin, vinblastine, and ifosfamide as salvage therapy.[6] Second-look surgery may be of benefit for a minority of patients whose tumor was not completely resected at the initial surgical procedure and who had teratomatous elements in their primary tumor.[11] Surgical resection of residual masses detected by clinical examination, by radiographic procedures, or at re-exploration should be undertaken since reversion to germ cell tumor or progressive teratoma has been described.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, Hatch KD, et al.: Chemotherapy of advanced dysgerminoma: trials of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 9 (11): 1950-5, 1991.

- Gershenson DM, Morris M, Cangir A, et al.: Treatment of malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 8 (4): 715-20, 1990.

- Wu PC, Huang RL, Lang JH, et al.: Treatment of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors with preservation of fertility: a report of 28 cases. Gynecol Oncol 40 (1): 2-6, 1991.

- Schwartz PE, Chambers SK, Chambers JT, et al.: Ovarian germ cell malignancies: the Yale University experience. Gynecol Oncol 45 (1): 26-31, 1992.

- Low JJ, Perrin LC, Crandon AJ, et al.: Conservative surgery to preserve ovarian function in patients with malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. A review of 74 cases. Cancer 89 (2): 391-8, 2000.

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, Moore DH, et al.: Cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin in advanced and recurrent ovarian germ-cell tumors. A trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med 111 (1): 22-7, 1989.

- Williams SD, Birch R, Einhorn LH, et al.: Treatment of disseminated germ-cell tumors with cisplatin, bleomycin, and either vinblastine or etoposide. N Engl J Med 316 (23): 1435-40, 1987.

- Taylor MH, Depetrillo AD, Turner AR: Vinblastine, bleomycin, and cisplatin in malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. Cancer 56 (6): 1341-9, 1985.

- Williams S, Blessing JA, Liao SY, et al.: Adjuvant therapy of ovarian germ cell tumors with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin: a trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 12 (4): 701-6, 1994.

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, DiSaia PJ, et al.: Second-look laparotomy in ovarian germ cell tumors: the gynecologic oncology group experience. Gynecol Oncol 52 (3): 287-91, 1994.

- Gershenson DM: The obsolescence of second-look laparotomy in the management of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol 52 (3): 283-5, 1994.

Treatment of Stage IV Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

Dysgerminomas

Treatment options for patients with stage IV dysgerminomas include:

- Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Clinical trials.

For patients with stage IV dysgerminoma, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended with removal of as much gross tumor in the abdomen and pelvis as can be done safely without resection of portions of the urinary tract or large segments of small or large bowel, although unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be considered in patients who wish to preserve fertility.[1,2] Chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) can cure the majority of such patients. Stage IV dysgerminoma is not treated with radiation therapy, but rather with chemotherapy, preferably with three to four courses of cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy such as BEP.[1] A second-look operation following treatment is rarely beneficial.

Other Germ Cell Tumors

Treatment options for patients with other stage IV germ cell tumors include:

- Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Clinical trials.

For patients with stage IV germ cell tumors other than pure dysgerminoma, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended with removal of as much tumor from the abdomen and pelvis as can be done safely without resection of the kidney or large segments of the small or large bowel. Patients who wish to preserve fertility can be treated with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Following maximal surgical debulking, three to four courses of cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy are indicated.[3,4] For patients with extensive intra-abdominal disease whose clinical condition precludes debulking surgery, chemotherapy can be considered prior to surgery. Patients who do not respond to a cisplatin and etoposide-based combination may still attain a durable remission with vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide or cisplatin, vinblastine, and ifosfamide as salvage therapy.[4]

Second-look surgery may be of benefit for a minority of patients whose tumor was not completely resected at the initial surgical procedure and who had teratomatous elements in their primary tumor.[5,6] Surgical resection of residual masses detected by clinical examination, by radiographic procedures, or at re-exploration should be undertaken since reversion to germ cell tumor or progressive teratoma has been described.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, Hatch KD, et al.: Chemotherapy of advanced dysgerminoma: trials of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 9 (11): 1950-5, 1991.

- Low JJ, Perrin LC, Crandon AJ, et al.: Conservative surgery to preserve ovarian function in patients with malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. A review of 74 cases. Cancer 89 (2): 391-8, 2000.

- Gershenson DM, Morris M, Cangir A, et al.: Treatment of malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 8 (4): 715-20, 1990.

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, Moore DH, et al.: Cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin in advanced and recurrent ovarian germ-cell tumors. A trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med 111 (1): 22-7, 1989.

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, DiSaia PJ, et al.: Second-look laparotomy in ovarian germ cell tumors: the gynecologic oncology group experience. Gynecol Oncol 52 (3): 287-91, 1994.

- Gershenson DM: The obsolescence of second-look laparotomy in the management of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol 52 (3): 283-5, 1994.

Treatment of Recurrent Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors

Dysgerminomas

Treatment options for patients with recurrent dysgerminomas include:

- Cisplatin-based chemotherapy has been used effectively for patients with recurrent dysgerminoma with and without adjuvant radiation therapy.[1]

- Patients with recurrent pure dysgerminoma of the ovary are candidates for clinical trials. Some consideration should be given to the use of high-dose regimens with rescue.

Other Germ Cell Tumors

Treatment options for patients with other recurrent germ cell tumors include:

- Patients with recurrent germ cell tumors of the ovary other than pure dysgerminoma should be treated with chemotherapy, the type of which is determined by previous treatment.[2] Radiation therapy is not effective in this setting. Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy is effective.[1,3,4] Patients who do not respond to a cisplatin-based combination may still attain a durable remission with vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide and cisplatin as salvage therapy.[1] Newer potential treatments include an ifosfamide combination [5] or high-dose chemotherapy and autologous marrow rescue.[6,7,8] Although the role of secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with recurrent or progressive ovarian germ cell tumors remains controversial, it may have some benefit for a select group of patients, particularly those with immature teratoma.[9] After maximal effort for surgical cytoreduction, chemotherapy should be considered.

- Patients with recurrent germ cell tumors of the ovary are candidates for clinical trials. Some consideration should be given to the use of high-dose regimens with rescue.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, Moore DH, et al.: Cisplatin, vinblastine, and bleomycin in advanced and recurrent ovarian germ-cell tumors. A trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med 111 (1): 22-7, 1989.

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, Hatch KD, et al.: Chemotherapy of advanced dysgerminoma: trials of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 9 (11): 1950-5, 1991.

- Williams SD, Birch R, Einhorn LH, et al.: Treatment of disseminated germ-cell tumors with cisplatin, bleomycin, and either vinblastine or etoposide. N Engl J Med 316 (23): 1435-40, 1987.

- Taylor MH, Depetrillo AD, Turner AR: Vinblastine, bleomycin, and cisplatin in malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. Cancer 56 (6): 1341-9, 1985.

- Munshi NC, Loehrer PJ, Roth BJ, et al.: Vinblastine, ifosfamide and cisplatin (VeIP) as second line chemotherapy in metastatic germ cell tumors (GCT). [Abstract] Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 9: A-520, 134, 1990.

- Broun ER, Nichols CR, Kneebone P, et al.: Long-term outcome of patients with relapsed and refractory germ cell tumors treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow rescue. Ann Intern Med 117 (2): 124-8, 1992.

- Motzer RJ, Bosl GJ: High-dose chemotherapy for resistant germ cell tumors: recent advances and future directions. J Natl Cancer Inst 84 (22): 1703-9, 1992.

- Mandanas RA, Saez RA, Epstein RB, et al.: Long-term results of autologous marrow transplantation for relapsed or refractory male or female germ cell tumors. Bone Marrow Transplant 21 (6): 569-76, 1998.

- Munkarah A, Gershenson DM, Levenback C, et al.: Salvage surgery for chemorefractory ovarian germ cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol 55 (2): 217-23, 1994.

Latest Updates to This Summary (09 / 18 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Editorial changes were made to this summary.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of ovarian germ cell tumors. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors Treatment are:

- Olga T. Filippova, MD (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center )

- Marina Stasenko, MD (New York University Medical Center)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/ovarian/hp/ovarian-germ-cell-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389449]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's Email Us.

Last Revised: 2024-09-18

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Learn how we develop our content.

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.